What was Claude walking into?

War for anyone is a state of confusion. For a teenage boy it’s a case of do as you’re told and you may stay alive. By now, your thoughts were all about survival. There were no heroics here.

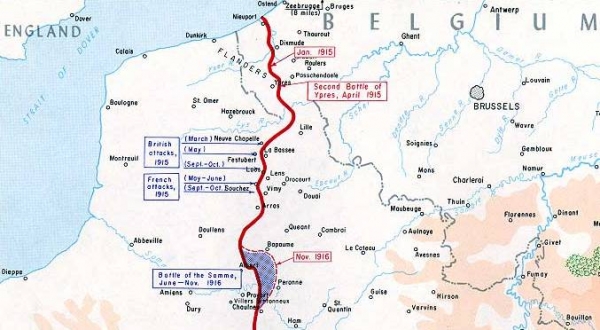

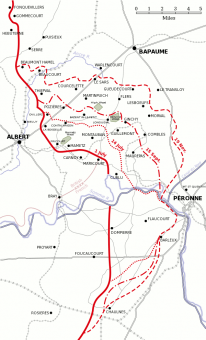

To paint the picture for the time, let’s look at the background for the Battle of the Somme and 17th Battalion activities around October and November.

Background for the Battle of the Somme

The Somme is a river in Picardy, northern France. The name Somme comes from a Celtic word meaning tranquillity. It is a little over 143km from Paris to the Somme.

The river is 245 km (152 mi) long, from its source in the high ground of the former Forest of Arrouaise at Fonsommes near Saint-Quentin, to the Bay of the Somme, in the English Channel. It lies in the geological syncline which also forms the Solent. This gives it a fairly constant and gentle gradient. 1

The Battle of the Somme was an attempt for the Allies to break through the German lines in northern France in 1916. The period of the engagement is recorded between the 1st July 1916 to 18th November 1916. It is regarded as one of the largest battles in the war with more than 1 million casualties.

The name Somme is synonymous with the word “Slaughter”. The opening day of battle saw around 60,000 British casualties.

The plan for the offensive in North France evolved out of Allied strategic discussions at Chantilly, Oise in December 1915. The Allied representatives agreed on a concerted offensive against the Germans in 1916.

The Somme offensive was to be the Anglo-French contribution to this general offensive and was intended to create a break in the German line which could then be exploited with a decisive blow. With the German attack on Verdun on the River Meuse in February 1916, the Allies were forced to adapt their plans.

The attack on 1 July, and the following campaign failed to appreciate the strength of the German defences. The British artillery was virtually ineffective and there was a lack of confidence in the ability of Britain’s volunteer army, which meant there was a distinct lack of imagination or innovation in the tactics employed.

Between the 23 July and 3 September, the ANZAC contribution to the Battle of the Somme was around Pozières and Mouquet Farm.

At Pozières between 23 July 1916 to 27 July the 1st Australian division suffered heavy losses from fighting, heavy artillery and counter-attacks. By the time it was relieved it had suffered 5,285 casualties.

The 2nd Australian Division took over and mounted two further attacks. These attacks, unsuccessful then successful, resulted in the seizure of German positions beyond the village. The Germans retaliated with heavy bombardments The 2nd Division was relieved on 6 August, having suffered 6,848 casualties.

Mouquet Farm cost the Australian 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions over 11,000 casualties. Not one of the attacks on the farm succeeded in capturing and holding it. The British advance eventually bypassed Mouquet Farm leaving it an isolated outpost. It fell on 27 September 1916.

Here is an animated presentation of the Battle of the Somme.

Battalion Life 1916

Claude was now part of the battalion. The best way to describe his life from the time of his entry is by reading, “The Story of the 17th Battalion in the Great War 1914-1918 by Keith McKenzie. 2.

October

- 1st and 5th Division take over the front line on sector 1 the 2nd division in reserve and the 4th behind it

- 4th and 1st division had been involved in a series of attacks

Conditions were boggy in the valley, and it was very hard to maintain supply lines.

November

- 5th division were withdrawn, 2nd division put in its place

- 17th Battalion marched out of Ribemont on the 4th November

- Marched to Montauban through Fricourt along congested road. Troops billeted in wooden huts. Conditions were windy and rainy.

November 6 and 7

- November 6th and 7th the 5th Division relieved the 7th Brigade. (The 7th had suffered heavy losses in useless attacks carried out in the heavy rain)

November 8

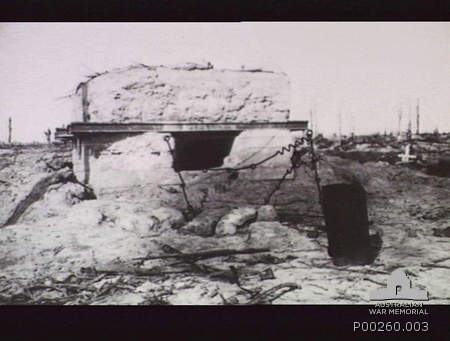

- For the next two days (November 8th and 9th) the Battalion remained in the trenches in conditions difficult to adequately describe.

- No overhead cover other than which could be “scrounged” from odd places for use as company or post headquarters, or by spreading the mens’ waterproof sheets over vertical “possies” scooped in the trench wall.

- The trenches themselves were feet deep in the mud, in which men were frequently bogged and had to be dug out with their shovels, often after much labour

- A Private of “D” Company was nearly ¾ hour in such a position before being released in state of semi-exhaustion.

- Extreme care had to be taken by men in order to keep the mechanism of their rifles from becoming clogged and their ammunition dry and clean.

- No hot food could be supplied, although hot tea was brought up in petrol tins.

- The troops have to carry on with dry rations, frequently fouled by contact with the mud.

- Communications with flank companies and the supports was difficult and hazardous, runners preferring to work along the top of the trenches at the risk of being sniped, to the slow exhausting process of ploughing through the gluey slime on the trench bottoms.

- Maintaining communications

- Repairing broken telephone lines

- Carrying messages between Battalion HQ and the front line. In this hazardous work the signalling-sergeant, D.H. White, who originally played the tenor horn in the band, and the Signaller J.T. O’Neill were killed, and two of their comrades, Private Wilson and Kelly, severely wounded.

- Sergeant M. Sharman, then a Battalion runner, has left a vivid description of the prevailing conditions.

Sergeant Sharman wrote….

I had a job as Battalion runner between headquarter and companies. Part of my job was to guide ration parties up to the front line on pitch-dark nights

So that I could find my way I kept my eyes on the muddy waste in order to pick up in order to pick up the track, which shone whenever the flares went up. I used to have a new pair of socks for every trip, otherwise I could not keep going. I got them from the number of dead men lying about, each of them had a spare pair in their haversack.

One of the blessings the mud brought was that the enemy shell-fire was largely ineffective; it nearly took a direct hit to bowl one over, because the shells just threw up a spout of mud when they landed.

I heard of one officer who had a Very flare pistol in hand when “Fritz” made a local attack. In the excitement of the moment he fired both once, only the pistol in his left hand was pointing downwards, the result being that he shot his own batman in the backside….

Getting up the line used to take hours; one got bogged and had to get out of one’s gum boots to get unstuck. Rifles and Lewis guns had to be wrapped up and the trench wall had to be constantly shovelled out when it collapsed. I made myself a shallow hole in No Man’s Land to save me from having to stand in the mud.

Back in rest areas it was as bad – Nissen hits with narrow duck-boards in between and mud everywhere. I remember seeing a man trying cross the road and getting stuck. Finally a mule had to be ridden out to him and he had to hang on to its tail to be pulled out.

In the front line, drinking water was scarce we had been warned not to use to use the water in shell-holes. That was all very well, but thirsty men had no option; some of us found a nice clean pool in No Man’s Land and after using it again and again, we found a dad Hun in it. Soon the mud gave way to intense cold; the water in our bottle froze, and the bully beef and tea had become ice cream by the time they reached the front line.”

The severity of the conditions are also recording in the diary of 393 Sapper CR Hill, HQ Signals 17th Batallion. Charles Rowland Hill was a New Zealander.

Hill’s diary also provides a wonderful insight into the time around Claude’s death. Part 2 has the details around the November period, which is found here.

Claude’s death

The picture of the 8th and 9th of November were now seen as some of the worst days in battle for the Somme. The rain, the mud made life unbearable. It also made it treacherous, as it made you a “sitting duck” for enemy observers to direct artillery fire your way.

So it was that Claude met his untimely death.

The Red Cross report states….

17th AIF B Co. 6 Platoon. E.C.Perkins, 4503 No Enquiry Report.“I saw Perkins killed by Shell fire on the 8th November near High Wood. His Body was buried in a shell hole outside the trench.” Reference: Cpl: G.H.Robinson, 2770, B Co 6Pl 3

Corporal Robinson’s account is very sad and sobering, Claude had become a victim of the constant shelling and barrage for which the first Western Front was known.

It was so sad that Claude at the age of 16 with only about 8 weeks of direct exposure to the Western Front had met his death. On the 8th of November the flower of youth was taken, a son was killed, a family heritage lost.

To understand what possibly could have happened to Claude’s body, we need to look in the records of his platoon commander, 2nd Lieutenant William G. Devitt 4 recorded by his commander Lieutenant Colonel R.G. Sadler along with the notations of his death in Keith McKenzie’s book “The Story of the Seventeenth Battalion in the Great War 1914–1918, P135” 5 Here is where the story continues.

November 9

The forward area was under constant and heavy shell-fine; most of which, luckily, fell to the rear of the front trenches. One shell, however, got right into B Company’s trench on the right, killing 2nd-Lieutenant W.G.Devitt and wounding Lieutenant J.J.Fay. Devitt was a promising officer of more than average ability. He had received his commission direct from the rank of Lance Corporal, for his courage and leadership during the Pozieres operations. The Seventeenth had lost a promising young officer.

Fay was ultimately invalided out of the army as a result of his head wound, and with his discharge, the Battalion was deprived of the services of one of its best platoon leaders, fearless as he was, meticulous in carrying out every detail of his duties. He had been a tower of strength to B Company, and was subsequently awarded the Military Cross.

Exhuming Pte. Perkins’ and Lt. Devitt’s bodies

Lieutenant Colonel Sadler noted for the record that they had to bury Devitt’s body at the back of the trench. Due to the nature of the battle they lost the position to the Germans and weren’t able to return to their for another 6 months; when that battle had shifted to the Allies, they were able to return to exhume the bodies and provide the soldiers with a more dignified burial.

There is every likelihood that Claude’s body was carried back from the front line with Devitt’s body as both Perkins’ and Devitt’s grave exhumation record has their names together.

Both soldiers were finally laid to rest in Grass Lane 3 miles, South west of Bapuame.

The wrap up of the 8th and 9th November

The Story of the Seventeenth Battalion in the Great War 1914–1918, P135″ 6 provides the closing comments of this battle.

“The two-day tour of duty in this unwholesome spot was also the occasion for an unusual experience, in the one, which it is doubtful, befell any other battalion of the AIF. It was in the form of a flammenwerfer attack made by a small party of Germans, just before daybreak, on a post held by No 16 platoon under sergeant R. Wilson and Corporal A. McDonald.

Wilson with a party of riflemen and bombers was holding a portion of the trench some 60 yards to the right of McDonald, who was in command of a Lewis gun section posted at the mouth of an unoccupied stretch of trench leading to the German lines. He had with him Corporal W.H. Rowe and Private T.A. Kelly, one of the lightest and toughest men in the Battalion.

The enemy made a feint attack on Wilson’s post while the flammenwerfer party stole along the disused part of the trench leading to McDonalds post. The enemy operator had the machine trained on McDonald and his gunners, who were intent on watching developments on their right and, therefore, had not seen the move. With a hiss and a roar the contents of the flammenwerfer were launched at the gunners, who instinctively ducked below the level of the parapet. But they kept their heads, and moving back along the trench they waited for the Germans to appear, when McDonald opened fire on them, with his gun. That finished the attack and the enemy withdrew under cover of semi-darkness, and bombs, which, however caused only one casualty, a man in Wilson’s party being slightly wounded.

It was not possible to ascertain whether the enemy had suffered any casualties, but the incident was a close shave for our men who had to withstand the terrific heat of the flames and were covered in oil-spots.

Some webbing equipment lying on the parapet was incinerated, and had the German, who operated the flammenwerfer used it from the top of the trench instead the bottom, it is certain that the Lewis gun section would have suffered a horrible death. But even this ordeal by semi-immersion in muddy drains, and exposure to chilling wind and soaking rain, that frequently induced a state of physical nausea, ended for the time being.

It was to be repeated on several occasions in the ensuing eight weeks, but none of the subsequent tours during that dreadful winter left such a deep impression on the minds of the men who were subjected to those unforgettable experiences.

During the night of the November 9/10, relief came in the form of the Nineteenth Battalion, and the Seventeenth withdrew to Carlton Camp about two miles distance.

Many men were so exhausted that they fell asleep in shell-holes, rejoining the unit after day-break. Morning revealed a camp of tents, stained with mud to camouflage them. There were no facilities for drying. Breakfast, and a roll-call was held, and one officer and 107 men were subsequently evacuated, the majority with trench-feet; others were suffering mainly from the effects of exposure. Many of the latter after receiving treatment at the Field Ambulance rejoined the Battalion in a day or two.

The Seventeenth “rested” at Carlton Camp all that day, and on the following morning sixty more of all ranks were given attention by the Field Ambulance.

At 4pm it moved to Mametz Camp, a collection of Nissen huts, designed to hold about one platoon to each hut.”

End of copy from P137.

References

- Adopted from “The River Somme” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/River_Somme ↩

- Keith McKenzie (1946). The Story of the Seventeenth Battalion in the Great War 1914–1918. Sydney: 17th Battalion AIF Association ↩

- Red Cross Report 17th AIF B Co. 6 Platoon. E.C.Perkins, 4503, Cpl: G.H.Robinson, 2770, B Co 6Pl ↩

- 2nd Lieutenant W.G. Devitt’s NAA Record http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/ItemDetail.aspx?Barcode=3503420 ↩

- The Story of the Seventeenth Battalion in the Great War 1914–1918, P135 ↩

- The Story of the Seventeenth Battalion in the Great War 1914–1918, P135 ↩