When the ANZACs left Gallipoli and moved to the Western Front in France, their previous experience helped in preparing for them for a different kind of war, however there was much to which they had to adapt.

Trench warfare on the Western Front

The new things that diggers were to meet were mustard gas attacks, the use of aircraft, flame throwers, large amounts of barbed wire, machine gun batteries and worst of all the artillery batteries that rained down piercing explosive shrapnel that literally tore bodies apart when they exploded.

The troops at Gallipoli had not met any of these tools of destruction to the extent that the Western Front would display.

It seems that the early divisions arriving France did not receive any training in trench warfare.

There were, however, a number of improvements that assisted the troops on the Western Front;

- Compared to Gallipoli, efficient medical and casualty evacuation

- Regular provision of hot meals and fresh vegetables

- The availability of leave to the rear areas along with leave to places such as Paris and England

- AIF Head Quarters (HQ), administration and convalescent units in the United Kingdom.

The Germans were a skilful and feared enemy. It seems that Australians had a hatred of the Germans for the way they conducted warfare.

As time moved on in the war, new arrivals received training in the fundamentals of trench warfare. Officers and Non Commissioned Officers (NCO’s) received training and instruction in gas warfare, use of machine guns, sniping, bombing, and the use of the trench mortar.

When it came to the arrival on the front, nothing could replace the fruits of experience being passed from those experienced campaigners to the new recruits joining the effort. However, the mortality rate in trench warfare was unspeakably high and “experienced” soldiers died at as rapid a rate as the new arrivals so survival became very much a matter of living on your wits.

It seems that there were three regions through which Claude would have passed through on his way to the front line.

Region 1

This included command and control areas, administration, logistics, key hospitals and medical dispatches. This was not geographically close to the front line.

Claude arrived in Étaples on 6th of September 1916. Étaples was the principal depot and transit camp for the British Expeditionary Force, the British army in France. 1

Claude’s records show that he marched into the 17th Battalion. No doubt the Battalion HQ 2 was located at Etaples.

Region 2

This region represents the area that leads to the actual field of action (region 3). This is where the battle had been, an area of devastation of artillery fire and the commencement of key trenches that led to the front line.

Region 3

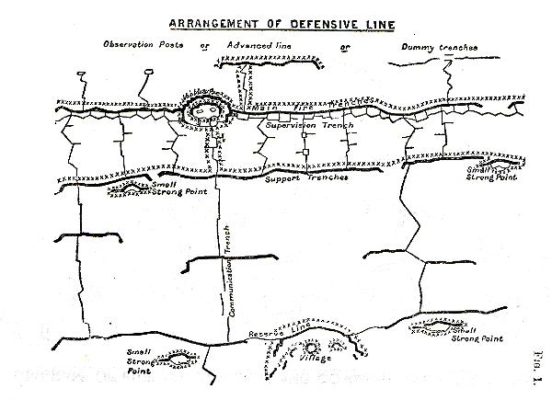

This is what is commonly known as the front line. Here he would have found the trenches where the battle was conducted. The diagram below outlines this area. 3 Chris Baker from “The Long long trial – A soldiers life in the trenches“, informed me that this was part of pamphlet provided to British Officers when they entered France.

Claude’s journey to the front line

Claude’s records show that when he marched into the Battalion on the 16th of September 1916, they were deployed to Belgium. This was to a quieter sector of the front. This would have provided the new recruits with an opportunity to gain an understanding of the requirements of fighting on the front line without being in the heat of the battle. The trip to the front line would have most probably been by train.

Joining the 17th Battalion on the front.

When he joined the on the 16th of September he met a group that has just been relieved from the front. 23 Battalion have taken their positions on the front line. 4 As the battalion moves away from the front line to a relief area he met the new unit.

There must have been a lot of conversation around the last front line deployment as, Private J.W.A. Jackson, 17th Battalion, originally from Gunbar, New South Wales, wins the Victoria Cross south-east of Bois Grenier, near Armentières, France.

Pte Jackson had returned safely, with a prisoner, from a raid in which several of the party had been seriously wounded in No Man’s Land.

He handed over the prisoner and immediately returned to aid one of the wounded men. He returned again to No Man’s Land and, with a Sergeant was assisting another wounded man when he was badly wounded in the arm by a shell (the arm was later amputated). The sergeant was knocked unconscious.

Jackson returned to the trenches and obtained medical help and again returned to No Man’s Land to find the sergeant and the wounded man they had helped, escorting one of them to safety.

By now, hearing of the numbers being killed, the story of the great adventure was probably turning into a story of fear. What was going through his mind? The noise of the shelling? The smell of death? The scenes of destruction all would have raised many questions in the mind of the of this 16-year-old teenager.

Claude was assigned to B Company 6th Platoon and No 9 section. From the records it indicates that his Section Leader was Corporal G.H.Robinson (2770) from Penshurst, Sydney, NSW and his Platoon Leader was nd Lieutenant William G. Devitt (2624) from Randwick, Sydney, NSW.

One of the nice things about the Australian Army structure was that it was based around the proximity and place of where people lived when they enlisted. This would have been a small comfort to know that the people around you came from and lived in the same region.

References

- Etaples – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etaples ↩

- Battalion Head Quarters – https://www.awm.gov.au/learn/understanding-military-structure/army/structure ↩

- The Long long trail – A soldier’s life in the trenches: http://www.1914-1918.net/intrenches.htm – copyright Chris Baker ↩

- https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/awm-media/collection/RCDIG1005338/bundled/RCDIG1005338.pdf ↩